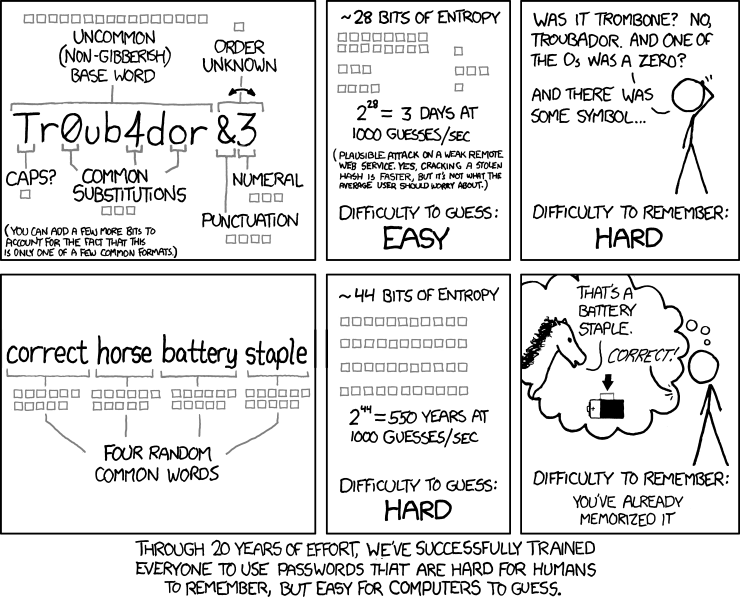

Title: Password Strength; alt-text: To anyone who understands information theory and security and is in an infuriating argument with someone who does not (possibly involving mixed case), I sincerely apologize.

This isn't good comic material, but it might just be good picto-blag material. It's kind of interesting information (whether it's accurate or not, I can't say), and it's clear that this is something that Randall likes and that he's willing to put some effort into. It's not funny, but he's not going for funny, so we'll let that go this time.

The caption is misleading, simply because for most of those twenty years, passwords that were hard to remember were also hard to crack. However, aside from that, the only real gripe I have with this strip is the know-it-all attitude Randall has about all this. The second parenthetical sentence in the second panel feels (to me) like his "Yes, centrifugal." remark in strip 852. It's just another way of saying, "I know what you're thinking, stupid plebeian reader, and I'm way ahead of you." And in the alt-text, when he says "To anyone who understands information theory and security," I can just hear the unspoken "like ME" after it. Yes, we know, Randall. Not everyone has the same domain of knowledge as you. Get over it.

Sometimes I wonder what it would be like to ram my massive rod up Randall's asshole. By "rod" I mean penis, btw. I have a massive one because I borrowed my father's. I figured he won't need it back any time soon now that he's dead.

ReplyDeleteThis analysis in this comic is completely useless because it presumes the attacker has complete knowledge about the password's structure, ie they know this. How could the attacker come to know all that information but not the password itself?

ReplyDeleteOr in other words, the attacker would be completely thwarted if the user simply changed the final number to a letter.

Also, though it may be correct to assert that a longer password is generally stronger, in this specific case the correct analysis would be that password 1 is susceptible only to bruteforce whereas password 2 could be solved using a sequential dictionary attack, likely known to people who have ever messed about with WPA security before. Knowing only the most basic facts about each (length of p1, number of words in p2) the number of combinations are 1: 8.5E20, 2: 1E20.

tl;dr: Randy takes two very strong passwords and gives attackers a huge advantage in cracking one to suit his own preconceived conclusion

Also, he scores a numeral as 3 bits of entropy. Where the fuck does that come from? 2^3 = 8, last I checked there were more digits than that. What a fucking asshole

The whole comic is retarded, because it assumes the attacker will know the format of the password but not the contents. If you assume the attacker knows nothing (which is to be expected for the "average user" as he says) then all his fancy labels go out the window.

ReplyDeleteTo people who actually know about information theory and security Randall just looks useless.

What? Why would you assume the attacker is a moron? Or even merely an "average user"?

ReplyDeleteAverage users have above-average attackers. Same as above-average users and below-average users. These attackers know that the format Randall described is quite common. It's hard to get statistics because anybody who answers questions about their password's formatting is somebody whose security practices should not be emulated. But I'm declaring, here on the INTERNET OF TRUTH, it's common.

Of course, more common still are passwords that are even less strong.

The alt-text reaffirms the kind of "Plebs, please feel free to fuck off" mentality reflected by the parentheticals.

ReplyDeleteIt's odd, his choice of which footnotes to include as parenthetical statements. He mentions that longer words can be used without significantly altering the results. But he doesn't bother explaining what is meant by gibberish (patterns that are phonetically valid in English but semantically empty?) or word (do names count?); why obscurity is a condition; why 16 bits are enough to capture the range of every "Uncommon (Non-Gibberish) Base Word," why only the first letter is subject to capitalization, why only one "common substitution" is considered for each letter....